A doctor once told me life mattered little if one did not die with dignity.

“Forget about being a hero or having a golden plaque on your grave, highlighting what a wonderful person you were,” he swatted the disappointment away with his hands. He combed his mustache with his index and thumb then fixed his eyeglasses. He exhaled, “it’s not that. I’ve seen it enough to understand it’s not that. By time you’re buried, no one remembers you.”

I didn’t reply. My gestures did. He smirked.

“Confusing?” I nodded. Good salespeople just nod along. “Everybody remembers the you before death, right? Good. Everybody remembers the death: the heart attack, the car crash, the quiet gasp in the middle of the night. I could go on, but neither of us wants to. But after death, we don’t remember much. And it’s fine. That’s what we are meant to do.”

And so, as his voice turned into a muffled mumble, I started thinking back. I thought about my brother and his best friend, Kyle. Back in ninth grade, there was a party in Kyle’s house. Booze, weed, a thumping bass. Kyle was a bit of both: high and drunk, cruzado we call it in my country (crossed senses). He got up and told everybody he was going to take a shower. They all laughed.

Seconds later, Kyle pulled the trigger on himself. My brother once described the sound as cracking a coconut with meat inside.

What happened next? I don’t want to remember. My brother doesn’t want to. He remembers Kyle the friend. He remembers opening the door and finding him–I know because of the recurring nightmares for the following years–but he doesn’t remember Kyle after he died. He doesn’t remember Kyle, the friend who betrayed him, because he doesn’t want to. Nobody does.

“And that’s why, Bernard, death is just as valuable as life,” he said.

“How do you want to go, doc?” I asked. He nodded, just once, and smiled with accomplishment.

“A small room, just my family, no rush, no stress, nothing. Just relief.” he said. Far too young to think about death, far too experienced to get away from it, at forty-four he’d probably seen more death than all my family put together. “No rain, no weather, no cold air, I hate cold air. Just four walls, a floor, a roof and silence.”

And so, there I was, in the country’s second biggest hospital, five minutes to seven a.m., just minutes away from fixing the orthopedic operating table. Once I had finished, I walked out to a long hallway that led to the exit. The disgusting radioactive green used in the walls drained my energy, as it always did, and the fluorescent lights hummed loudly. Then cold air seeped into my pants and tickled up my legs.

Damn, doc, you were right.

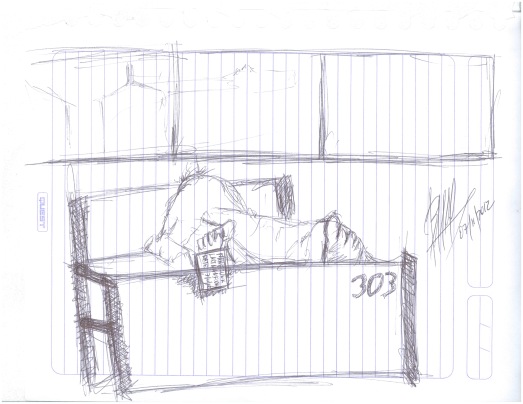

I turned to my right after reaching the corner and stopped. I gasped but no one saw me; I was alone. Just me and stretcher 303. There was a white sheet resting over a lump of branches and cylinders, a patch of gray hair peeked from the top and nothing moved. I shook it off. It’s just a hospital. Someone would come.

At three thirty in the afternoon I got a call from a close friend in the hospital; I’d left my tool belt. I rushed back to reclaim what was mine. So happy to see all my tools in place, I completely forgotten about the corner. Again I stopped. There he was, 303.

To my right, no one. To my left, no one. Just the speaker in the corner: Operating Room assistant to the third floor. Operating Room assistant to the third floor. I inched closer, peeking about like a shoplifter eyeing its bounty, until I reached the foot of the bed.

Name: Unknown.

Last Name: Unknown.

I don’t know but at that moment I had the urged to photograph him. I knew I couldn’t: it’s against the law. So I checked around again and pulled out my notebook and a pen. I sketched it rapidly.

Damn, Doc, you were right. I never want to be stretcher 303.